Stop Building Products. Start Architecting Markets

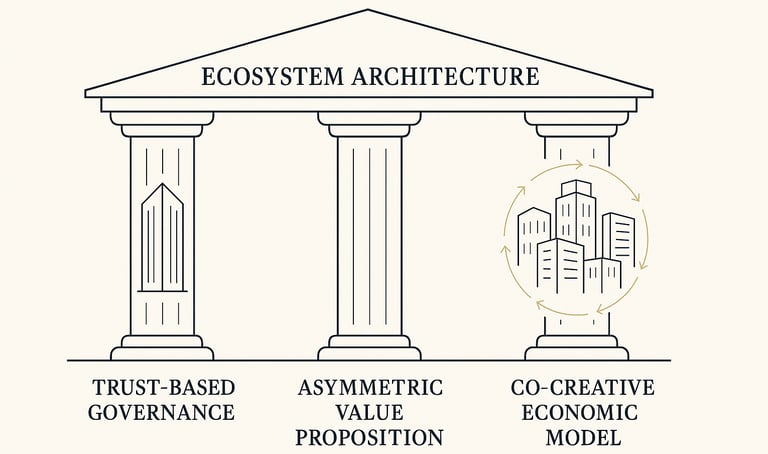

Most ecosystem initiatives fail not because of technology, but because of broken economic governance. This article argues that scaling a platform requires an 'Institutional Architecture' approach—moving beyond feature roadmaps to design trust-based governance, asymmetric value propositions, and co-creative economic models. A blueprint for architects responsible for sustainable market scale.

Ruchir Saurabh

8/12/20258 min read

In an internal review meeting, a team had delivered flawlessly: timelines were met, KPIs were exceeded, and network uptime was beyond expectation. By every metric on the slides, it was a "mission accomplished." Yet I found myself asking a question that wasn't on the slides: "Have we truly created enduring value, or have we just gotten better at optimizing what we already do?"

That moment crystallized for me the central paradox of modern business. We train our leaders to be excellent product managers, but the market is asking them to be architects.

Most ecosystem failures follow a common pattern that traces back to that meeting. We confuse the appearance of a platform (APIs, a marketplace) with the architecture of a market (governance, incentives, rules). The team in the review was doing exactly what they were trained to do:

They were organized to optimize for control, while ecosystems require shared governance.

They measured success in product adoption, while ecosystems rise or fall on partner economics.

They allocated capital to functionality, when ecosystems require investment in institutions.

The consequence is an "empty city": a platform with a flurry of activity but no real economic velocity. Microsoft’s Windows Phone is a perfect, cautionary example. Despite a strong product and billions in investment, it lacked a compelling value proposition for developers. Without apps, users didn't join; without users, developers stayed away. The issue wasn't the product; it was the absence of ecosystem.

“The real competitive advantage lies not in building the tallest skyscraper, but in designing the most resilient city.”

The Ecosystem Architecture Framework

The answer to the question of building enduring value, lies in the principles and practice of "Ecosystem Architecture."

Successful ecosystems don't scale by accident. They scale when leaders deliberately design the conditions for co-creation. Through my study of leading platforms, I've identified three pillars that consistently distinguish successful ecosystems from failed ones. These pillars are mutually reinforcing; weakness in one, destabilizes the entire system.

Pillar 1: Trust-Based Governance (The Rules of the Market)

Trust is the first enabling condition. Because participants transact under uncertainty, the platform must create trust through its governance. Effective governance, in my view, includes:

Clear participation criteria.

Enforceable quality and security standards.

Transparent rule enforcement.

Without this, platforms collapse into low-quality markets where fraud and inconsistency drive away high-value participants.

Case Example: Apple

In 2024, Apple reviewed more than 7.7 million app submissions and rejected 1.9 million for failing to meet safety and privacy standards. I don't see these rejections as overhead—I see them as investments in trust. That trust enables billions of dollars in secure transactions.

Case Example: Salesforce AppExchange

Salesforce’s governance model performs rigorous security checks for enterprise apps. This reduces risk for CIOs and accelerates adoption. Here, governance becomes a shared infrastructure that lowers transaction costs for everyone.

“Governance is not control—it is market design.”

Pillar 2: The Asymmetric Value Proposition (The "Magnet")

Trust brings participants to the doorstep. Asymmetry brings them inside. In my experience, partners only join an ecosystem when the value they receive is structurally greater than the cost of participation.

An asymmetric "magnet" typically offers:

Distribution partners cannot achieve alone.

Access to a trusted, high-value user base.

Dramatically lower acquisition or integration costs.

The key is that the platform’s marginal cost of providing this value is near zero, while the partner’s marginal benefit is substantial. This is what solves the "cold start" problem.

Case Example: Apple’s $1.3 Trillion Ecosystem

More than 90% of the $1.3 trillion transacted in Apple’s ecosystem in 2024 generated no commission for Apple. This near-free access to a global, trusted marketplace is one of the strongest magnets in the digital economy.

Case Example: Shopify

Shopify provides merchants with global commerce infrastructure—payments, logistics, compliance—at a fraction of the cost of building it independently. This is a textbook asymmetric incentive: Shopify invests once; millions of merchants benefit.

Pillar 3: The Co-Creative Economic Model (Sharing the Wealth)

Ecosystems thrive only when their partners thrive. Extractive models drive partners to defect or "multi-home" (list on a rival's platform); co-creative models align economic incentives for the long term.

Case Example: Microsoft’s 1:10 Multiplier

According to IDC, for every $1 Microsoft earns, software partners earn nearly $11. This multiplier incentivizes partners to innovate on Azure, expanding the platform in ways Microsoft could never achieve alone.

Case Example: AWS Marketplace

A Forrester study found that partners selling through AWS Marketplace close deals 40% faster and with 80% larger average values. AWS’s billing and compliance infrastructure removes friction and increases partner profitability—turning the marketplace into an economic engine, not just a product feature.

“Partner prosperity is platform defensibility.”

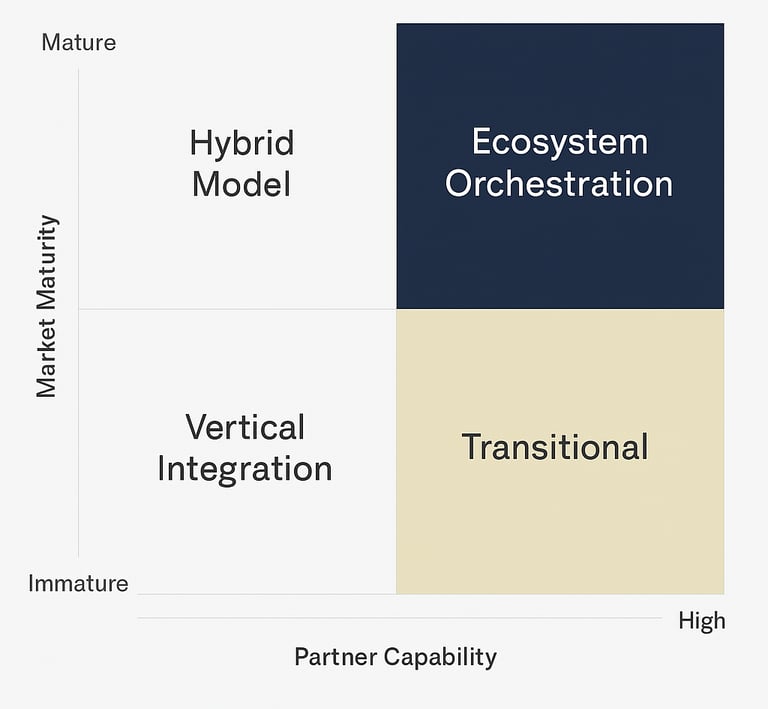

When an Ecosystem Is the Wrong Answer

This playbook is powerful, but it is not universal. As a leader, it's just as important to know when not to use it. In markets with immature suppliers, unstable technology, or high intellectual-property risk, I believe vertical integration is often the superior, more rational choice. You cannot orchestrate what does not yet exist.

Attempting to build an "open" ecosystem in such a market isn't just a bad strategy; it's often a fatal one. It exposes your core innovation to partners who can't deliver quality, creates a fragmented and terrible customer experience, and slows your iteration speed to a crawl. When the core technology is still in flux, you need a tight, closed loop between engineering and the customer—something an open ecosystem, by definition, cannot provide.

Case Example: Tesla and BYD

Both companies vertically integrated battery chemistry, power electronics, and software because external capabilities did not exist at the required quality or scale. The traditional auto supply chain was optimized for a century of combustion engines; it had no expertise in high-density battery chemistry or vehicle operating systems. For Tesla to deliver its core product promise, it had to build those capabilities itself. Opening these systems prematurely would have compromised the product and slowed innovation to a crawl.

As markets mature, a firm can pivot. Tesla’s decision to open its NACS charging standard is a masterful example of this two-step logic.

First, build vertically: Create a closed, superior asset (the charging network) to solve the primary customer problem (range anxiety) and win the market.

Then, open strategically: Once that asset becomes the dominant standard, open it as a platform. This move flips a massive cost center into a new, high-margin revenue stream. It forces competitors to adopt your standard, cementing your platform as the central infrastructure for the entire industry. It's a brilliant pivot from a closed product to an open platform, but the timing was everything.

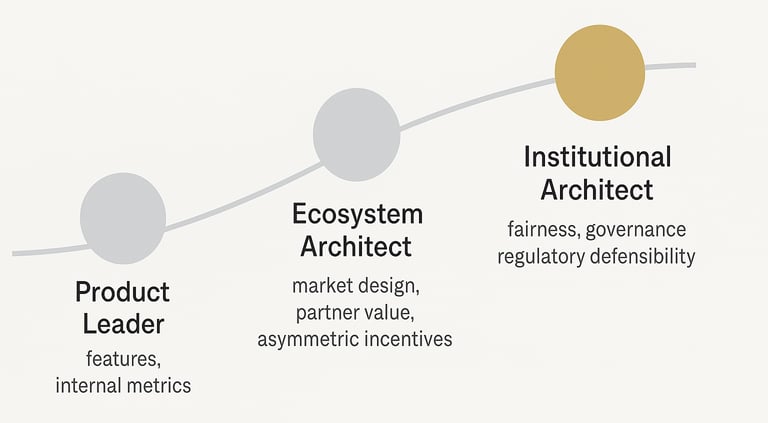

The New Mandate: From Ecosystem Architect to Institutional Architect

Just as leaders are beginning to master the skills of an Ecosystem Architect, the ground is shifting. A fourth force now shapes strategy, one that makes the architect's job infinitely more complex: regulation. This isn't just a compliance issue; it's a fundamental rewriting of the rules of market design. The EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA) and U.S. antitrust actions are not just imposing fines; they are actively targeting the very mechanisms—the "interlocking patterns" of governance, integration, and incentives—that made leading platforms successful.

This introduces a new paradox, one that lives at the intersection of strategy and policy:

What the strategy team calls "brilliant integration" (like a seamless app store payment system), regulators may now call "self-preferencing" or "tying."

What users call "safety and simplicity" (like a curated, 'walled garden' app store), regulators may call "anticompetitive foreclosure."

The very tools that built the most valuable companies in the world are now their greatest liabilities. This means that as leaders, we must now design for fairness, openness, and contestability from day one. Compliance can no longer be a reactive checklist we hand to the legal department; it must become a core design principle.

This new reality doesn't replace the need for an Ecosystem Architect; it evolves the role. The emerging leadership capability is what I call the Institutional Architecture. This leader is someone who can design a system that is not only economically compelling and operationally scalable, but also regulatorily defensible. In practical terms, this requires integrating strategists, governance experts, and public policy teams from the very beginning, moving from a mindset of "building a moat" to "building a defensible city." The Institutional Architect must also build internal systems that prove fairness—such as running "contestability audits" to find and fix self-preferencing before a regulator does, or establishing partner councils to give participants a real voice. This is a profound shift from pure, profit-maximizing design to a more "statesman-like" approach of building a fair, lasting institution.

The Strategic Filters

That internal review was a turning point. It fundamentally changed how I evaluate strategic opportunities. Instead of just focusing on product KPIs—the "what"—focus has shifted to the architectural principles—the "how."

These are the strategic filters I now apply to any new initiative, whether it's my own or one I'm evaluating. It's no longer a prescriptive checklist for a team, but a way of seeing the business:

Partner Readiness vs. Partner Creation:

I ask: Are the capable, high-quality partners we need already in the market? Or is the real (and much harder) strategy to build that partner base from scratch? Answering this honestly reveals the true timeline and capital required.

The Asymmetric "Magnet" vs. Paid Incentives:

I ask: Are we offering a structural incentive—like access to our distribution, data, or trusted user base—that partners can't get elsewhere? Or is our "ecosystem" just a temporary budget to pay for partners? One is a durable moat; the other is a leaking bucket.

Governance as a Principle vs. Governance as Control:

I ask: Are we truly prepared to enforce rules that build trust, even if it means rejecting a high-revenue (but low-quality) partner in the short term? If the default answer is to always maximize our own control, we will fail to build trust.

Regulatory Design vs. Regulatory Defence:

I ask: Did we design this for fairness and contestability from day one? Or are we building a model that will inevitably become a legal and regulatory battle? The first is strategic architecture; the second is a tactical trap.

Internal Alignment vs. Internal Conflict:

I ask: Are our internal incentives, especially sales commissions and KPIs, set up to reward partner success? Or will our own culture—which is built to sell our products—instinctively kill this initiative from within?

If the answers to these questions are "no," or "we haven't thought about that," I've learned that the initiative is almost certain to fail. It shows we are still thinking like product builders, not institutional architects.

Conclusion

That nagging question I had in that review—whether we were building real value or just optimizing—is, I’ve come to believe, the fundamental difference between product management and institutional leadership. Optimizing is tactical and internal; it’s about making the existing machine run better. Building enduring value is strategic and architectural; it's about designing a new machine that creates a gravitational pull.

Product excellence is no longer enough; it's just the ticket to the game. In my experience, the next era of competition will belong to firms that master Institutional Architecture. The old moats—product features, supply chains—are evaporating. The new, durable moats are institutional: the trust of your market, the profitability of your partners, and the fairness and transparency of your rules.

This is the shift from being a product builder to being an institutional architect. It's a journey that requires a different way of seeing, of measuring, and of leading. It is the ultimate challenge: to stop just building a "thing" and to start designing a self-sustaining market that builds shared prosperity.

Thoughts? Debate this article on LinkedIn

Follow Me

Contact

© 2025 Ruchir Saurabh. All Rights Reserved.